Wetland-Margin Lawn & Tree Management for Carol Stream

Expertise managing flood-plain soils and seasonal high water tables.

Expertise managing flood-plain soils and seasonal high water tables.

Carol Stream properties near the East Branch DuPage River face a unique challenge: seasonal waterlogging. Every spring (April–May), snowmelt and early rains raise the water table above 24 inches, leaving root zones oxygen-depleted for weeks. Standard lawn grasses cannot tolerate waterlogging; their shallow root systems suffocate in anaerobic soils, and grass production collapses. Into that void moves sedge — spike sedge, three-square sedge, and other Carex and Eleocharis species that thrive in saturated conditions where grass fails. Sedge spreads via underground rhizomes and quickly dominates properties, creating a dense, un-attractive stand that resists standard herbicides.

Our program begins with water table assessment. We measure depth and seasonality using soil cores and rainfall data, then recommend species appropriate to your property's hydrology. For properties with water tables 12–18 inches below the surface for 2–4 weeks in spring, we use flood-tolerant tall fescue blended with fine fescue species (chewings fescue, hard fescue). For permanent wetland margins or very tight flood plains, we recommend accepting sedge or converting to native wetland plantings (sedges and rushes) rather than fighting the site's natural ecology.

Existing sedge infestations are attacked with sedge-specific herbicides (quinclorac, bentazon) applied in late May and early June when sedge is actively transpiring and moving carbohydrates to the rhizome. Multiple applications (3–4 spaced 2 weeks apart) are often needed. Combined with fall aeration (after the water table drops) and overseeding with flood-tolerant species, sedge suppression can be achieved over one full growing season. Moss control follows a similar strategy: drainage improvement first, then herbicide treatment.

Some local properties benefit from subsurface drainage installation. A French drain system (perforated pipe in gravel) intercepts groundwater and directs flow to a discharge point (storm sewer, daylight outlet, or dry well). Installation costs range from $3,000–$8,000 depending on property size and soil conditions. We assess water table depth using soil cores and recommend drainage if water table stays above 12 inches for more than 3–4 weeks in spring. Alternatively, raising the lawn elevation by 6–12 inches (referred to as surface grading) can relocate the turf area above the seasonal high-water-table zone. Call 224-415-3698 for a site evaluation.

"Our lawn was just a sedge patch every spring. We thought it was hopeless until Greener Living explained the water table issue and switched us to tall fescue with sedge treatment. Two seasons later, we actually have grass instead of sedge. Huge improvement."

— M. & E. Liu, 60188

"We had new oak and maple planted after an old tree came down, but they were yellow and struggling in our clay. Once we got them elevated above the water table and Greener Living did the deep-root feeding, recovery was fast. They're thriving now."

— J. Klinger, 60188

"The moss came back every year until we aerated in late summer and treated it. Grener Living explained that moss loves wet, compacted clay. Once we opened up the soil, moss stopped returning. Great explanation, better results."

— D. & S. Washington, 60188

local properties benefit from integrated approaches addressing both water management and plant selection:

Tell us about wet patches, sedge presence, moss problems, or drainage concerns — we'll provide site-specific recommendations.

We measure depth seasonally and recommend species, aeration timing, and drainage accordingly.

We identify sedge species and apply species-specific herbicides at the right phenological stage.

We assess French drain feasibility and recommend final disposal options.

Bald cypress, river birch, and pin oak thrive in Carol Stream's seasonal inundation.

Local sits at the intersection of suburban development and floodplain ecology. Managing lawns here requires understanding both hydrology and plant physiology — standard programs will fail. We analyze your site's water table depth, timing, and duration; recommend appropriate species; and design drainage if needed. This isn't a one-size-fits-all operation. Every Carol Stream property is different.

Carol Stream's foundation is flood-plain clay deposited by Pleistocene glacial meltwater. The East Branch DuPage River, flowing southeast, has carved a valley with poorly-drained clay soils on either bank. These clays (montmorillonite and illite minerals) have extremely low permeability — water moves through the profile at rates of 0.01 inches per hour or slower. Every spring, snowmelt and early rains saturate the clay to depths of 24–36 inches, creating a seasonal high-water-table zone. In normal years, this zone remains saturated April–June. In wet years (40+ inches annual precipitation), saturation can persist July–August. Grass roots cannot tolerate this environment; they require 15–20% air-filled porosity for respiration. Once porosity drops below 10% (as happens in saturated clay), grass roots stop growing and begin dying within days. Into that anaerobic void, sedge and moss colonize.

Sedges are monocots (like grasses) but with different physiological capabilities. Spike sedge (Eleocharis) and three-square sedge (Schoenoplectus) have aerenchyma tissues — specialized tubes running through stems and roots that transport oxygen from the air directly to anaerobic root zones. This allows sedge roots to function in permanently waterlogged soils where grass roots die. Once grass collapses from waterlogging, sedge rhizomes expand into the empty niche. Sedge spreads clonally; a single sedge ramět can generate dozens of tillers connected by rhizomes, creating dense monocultures. Standard broadleaf herbicides (2,4-D, dicamba) don't translocate through sedge vascular tissue effectively; sedge-specific herbicides must be used. Late-spring applications work best because sedge is moving carbohydrates from rhizomes to shoots, ensuring excellent herbicide transduction. We apply sedge herbicides (quinclorac or bentazon) in late May and early June, then repeat applications every 2 weeks through July to suppress multiple sedge cohorts.

Flood-tolerant turf species are few. Tall fescue tolerates 7–14 days of saturation without fatal damage; soils can remain flooded longer if temperatures are cool and respiration rates are low. Fine fescue species (chewings fescue, hard fescue) show even greater flood tolerance — some cultivars survive 30+ days of continuous saturation. Kentucky bluegrass has poor flood tolerance; standard cultivars begin dying within 3–5 days of saturation. However, some experimental bluegrass cultivars (developed at University of Minnesota and USDA-ARS) show improved tolerance, though these remain uncommon in commercial seed mixes. For local properties with water tables 12–18 inches below the surface for 2–4 weeks in spring, a blend of tall fescue (60%) + fine fescues (40%) is optimal. For properties with water tables <12 inches for 4+ weeks, consider native wetland plantings or accepting sedge as a permanent feature.

Pythium and Phytophthora (water molds, oomycetes) thrive in waterlogged soils. These pathogens are not true fungi; they are fungal-like organisms with different cell wall chemistry (cellulose instead of chitin) that makes them resistant to fungal herbicides. Water molds release zoospores in water films; these spores swim through anaerobic soil and invade plant roots, causing rapid necrosis. Pythium attack on turf roots produces the classic "root rot" symptom: above-ground wilting despite adequate soil moisture. Pythium attacks new tree plantings with particular ferocity in waterlogged sites. At planting, elevate the root ball 4–6 inches above grade and backfill with well-draining compost to avoid creating a water-logged micro-site around the transplant. Apply phosphonite or copper fungicide drenches to the root zone in spring and early summer to suppress water mold colonization. This is essential for newly establishing trees in Carol Stream.

Waterlogged soils develop anoxic conditions where iron and manganese become chemically reduced (Fe²⁺ and Mn²⁺) and accumulate to toxic levels. These reduced minerals stain the soil gray-blue (gleying). Aeration introduces oxygen, which allows naturally-occurring bacteria to re-oxidize these toxic forms back into insoluble oxides, restoring soil health. However, aeration timing is critical: aeration during spring saturation can worsen problems by creating pathways for water to move deeper. We aerate local properties only in late August–September, after the water table drops below 12 inches. At that timing, aeration breaks compaction, improves oxygen diffusion, and prepares the soil for fall seedling establishment without risk of exacerbating saturation. Multiple aeration passes (200+ cores per 1,000 sq ft) provide better compaction relief than single passes.

French drain systems intercept groundwater moving through clay layers before it reaches the lawn root zone. A French drain consists of a perforated pipe (usually 4–6 inch diameter) buried in a gravel trench 12–18 inches below the lawn surface. The pipe is wrapped in landscape fabric to prevent clay particles from clogging perforations. Water enters the pipe through perforations and flows along the pipe slope to a discharge point (daylighted outlet, culvert, storm sewer, or dry well). Installation costs range $3,000–$8,000 depending on property length and soil conditions. We assess feasibility using soil cores and measuring seasonal water table depth. If the water table is within 12 inches of the surface for 3+ weeks April–June, a French drain may prevent that saturation. However, for very tight flood plains (water table 6–8 inches below surface), drains alone may not solve the problem; combine drains with surface grading (raising the lawn 6–12 inches) for better results.

Moss outcompetes grass in waterlogged, shaded, acidic soil. Moss has no roots; instead, it absorbs water and nutrients directly through its leaf surface (protonemata). This allows moss to thrive even when soil oxygen is depleted (grass roots need soil oxygen). Spring waterlogging combined with shade from deciduous trees creates ideal moss habitat. Local properties near tree canopies are particularly susceptible to moss resurgence. Control requires addressing the underlying cause: improving drainage (aeration + soil amendment). Moss-specific herbicides (ferrous sulfate, sulphate of ammonia) burn moss but don't address waterlogging, so moss returns annually. We recommend combined approaches: fall aeration to improve drainage, lower-limb tree pruning for light, thatch removal (vertical mowing), and moss herbicide treatment. Without drainage improvement, moss becomes a permanent feature best accepted rather than fought.

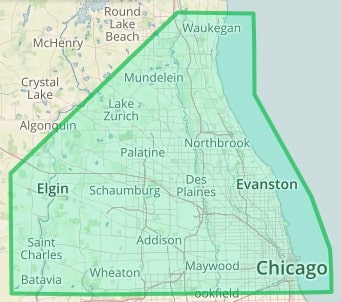

We also serve properties in these surrounding towns: