Tall Fescue Turf Management & Tree Care in Bartlett

The grass really is Greener the way we treat it.

The grass really is Greener the way we treat it.

Bartlett sits at a soil boundary. Moving west from Chicago's suburban core, you transition from acidic glacial-till clay (pH 6.0–6.5) into the alkaline loam and chalk-derived soils of DuPage County (pH 7.2–7.8). That shift changes everything about how turf behaves. Standard bluegrass lawns struggle in high-pH conditions — iron and manganese become chemically locked in the soil solution, unavailable to plant roots. Magnesium deficiency shows up as chlorosis in late spring. Meanwhile, the root systems of Kentucky bluegrass max out around 24 inches, unable to reach moisture reserves in deeper soil layers during July dry spells.

Our program prioritizes tall fescue, a deep-rooting species that handles alkaline conditions and heat stress far better than bluegrass alone. We blend it with improved bluegrass cultivars for color and turf density, creating a hybrid stand that performs through the extremes of a DuPage County growing season. Every visit includes a complete aeration-and-thatch assessment — compacted building soils in newer subdivisions and thatch buildup in established neighborhoods require different feeding schedules and product choices. We walk your property, evaluate soil structure, and adjust our granular blend and liquid spray formulations accordingly.

Broadleaf weeds in alkaline soils — especially clover and plantain — thrive when nitrogen is insufficient. We front-load nitrogen in spring and early summer, then dial it back in July–August to reduce fungal susceptibility during peak heat stress. Fall nitrogen (September–October) is applied as soluble granules that drive both shoot growth and root carbohydrate storage for winter dormancy.

Japanese beetle grubs emerge and begin feeding on fine turf roots in July–August, causing irregular brown patches that peel like carpet. Prevention applied in late May–early June kills first-instar larvae before they establish in the thatch-root interface. We time applications to the Forsythia stage (mid-May) when soil accumulates GDD heat units triggering beetle oviposition. One preventive application buys you the entire season. Properties with a prior grub history or those bordering wooded areas face higher beetle populations — we scout these accounts and recommend treatment to customers proactively.

"We just moved to a new subdivision off Route 59 and the builder's quick lawn was all clover within one season. Greener Living showed us that our soil was high-pH and not suited to straight bluegrass. After switching to tall fescue and adding spring nitrogen, the clover is gone and we have a thick, dark green yard for the first time."

— R. & T. Chen, 60103

"Had major grub damage two years running. Their preventive in June (right after Forsythia bloom) stopped the problem completely. They explained the window is tight and missing May means waiting another year. Now we're on annual prevention and pay a fraction of what it would cost to reseed."

— L. Thompson, 60103

"Our 40-year-old oak was struggling — yellow leaves despite fertilizer. They deep-root fed it with chelated iron and we saw color recovery within weeks. The technician explained that our well water is pH 8.2 and iron binds in that chemistry. Smart explanation, smart fix."

— J. & K. Vogel, 60024

local properties benefit from integrated programs that address both turf and woody plants:

Share your property details — soil conditions, past problems, visible issues — and we'll send a site-specific recommendation and quote.

Caymen personally reviews every Bartlett property assessment and signs off on treatment plans.

pH-adjusted formulations, soil-specific nutrient blends, and horticultural insight guide every decision.

Weeds breakthrough or grub damage appears? We return at no additional charge.

Pay per visit. Pause, skip, or cancel anytime with zero penalty.

Your property's mix of new construction and established neighborhoods requires turf specialists who understand soil chemistry. We are small enough to customize every program and large enough to handle complex multi-property accounts. When you call, you speak directly with the owner about your specific situation — no regional call center, no preset packages forced onto different soil types.

Chicagoland sits at a pedological boundary between Cook County's acidic glacial soils and DuPage County's post-glacial alkaline loam. Moving west across Route 59, soil pH rises from 6.2 to 7.8. That shift changes every aspect of turf management. Kentucky bluegrass, dominant in acidic soils, shows iron chlorosis in pH 7.2+ conditions; available iron precipitates into ferric oxide forms plant roots cannot absorb. Magnesium deficiency appears as interveinal chlorosis on oldest leaves in late spring. Meanwhile, bluegrass shallow root systems (18–24 inches) fail to reach moisture reserves in deeper local soils during July dry spells. Tall fescue, with roots to 40+ inches and better alkaline tolerance, outperforms bluegrass in these conditions. Our program emphasizes tall fescue blended with improved bluegrass cultivars that handle higher pH better than standard types.

Japanese beetle adult emergence in the area occurs around June 20th, triggered by accumulated soil heat units (GDD). Females begin oviposition immediately, laying eggs in the thatch-soil interface. Eggs hatch 10–14 days later, and first-instar grubs commence feeding on fine turf roots July through August. By fall, grubs have reached third-instar and burrowed deeper into soil to overwinter. A preventive applied in late May–early June kills first-instar larvae immediately after hatch, before they establish in the root zone. If preventive is delayed until July, grubs are already established 2–3 inches below the lawn surface, beyond most preventive reach. Established subdivisions with deep thatch layers are prime habitat; we scout these areas in spring and recommend prevention to vulnerable accounts. Learn more about our grub program.

Bartlett's rapid western expansion means many properties were built on undisturbed prairie soils moved and compacted during grading. That mechanical compaction creates a dense layer at 3–6 inches that severely restricts root penetration and water infiltration. Standard granular fertility programs cannot overcome structural compaction alone. Core aeration — mechanical removal of 2–3 inch soil plugs on 2–3 inch spacing — relieves compaction and creates pathways for root growth and water infiltration. Fall aeration timing (September–early October) is ideal: soil moisture is still abundant from summer rains, but daytime heat has dropped below 80 degrees, reducing transplant shock on new seedlings. We immediately overseed with improved tall fescue and bluegrass cultivars selected for DuPage County conditions. By November, new seedlings have developed secondary roots and can survive dormancy.

Newly planted shade trees — red maple, sugar maple, green ash, white oak — show severe chlorosis in Bartlett's alkaline soils. Root-zone iron becomes chemically bound and unavailable despite abundant soil iron. The condition worsens if irrigation water is drawn from municipal wells (typical pH 8.0–8.5). Deep-root feeding with chelated iron products bypasses the soil chemistry and deposits available iron directly into the tree's vascular tissues. Results are visible within 3–4 weeks: new leaf emergence shows normal green coloration instead of yellow interveinal pattern. We also apply dormant oil in March to suppress scale insects and spider mites that exploit weakened trees. Mature oaks in older local developments face anthracnose and decline exacerbated by compacted soil around their base (from foot traffic and root space limitation) and road salt spray from nearby streets.

Nitrogen management in Bartlett's high-pH soils differs from neutral or acidic-soil programs. Spring and early summer nitrogen (March–June) is applied as soluble granules with full strength — early growth momentum minimizes broadleaf weed invasion (clover and plantain thrive in low-nitrogen conditions). July–August nitrogen is reduced to slow-release products applied at lighter rates to avoid stimulating disease susceptibility during peak heat stress. Fall nitrogen (September–October) returns to full soluble rates, driving both shoot growth and root carbohydrate storage for winter survival. This tri-phase nitrogen strategy — aggressive early, conservative mid-summer, aggressive late — maximizes turf density and color while managing both weed and disease pressure across the growing season.

Clover infestations in Bartlett's alkaline soils respond inconsistently to standard broadleaf sprays applied in spring. The issue: clover is a biennial legume that shifts resource allocation seasonally. Spring clover is investing heavily in shoot growth and new leaf production; herbicides applied then are mobile and translocate to the root. But root-zone pH and cool soil temperatures reduce herbicide biological activity. Fall clover (September–October) has shifted resources to roots for overwintering; a fluroxypyr-based herbicide applied then translocates to those heavily-invested roots and causes far more effective kill. We use a two-application strategy on heavy infestations: lightweight spring spot-treat to reduce clover seed head formation, then full-coverage fall spray when clover is most vulnerable. Fall treatments persist longer in alkaline soils because cooler temperatures extend the herbicide biological window.

July and August in the area bring predictable heat stress challenges. Temperatures exceed 85 degrees for 20+ days each month, and rainfall often drops below 2 inches. Tall fescue, with its deeper root system, handles this pressure better than bluegrass alone. However, even fescue benefits from adjusted management during peak stress. We reduce nitrogen applications in July and August to avoid stimulating tender new growth that fungal diseases exploit under heat-and-humidity conditions. Instead, we shift to potassium-weighted formulations that toughen cell walls and improve plant water retention. We also recommend deeper but less frequent irrigation (1 inch per week, applied once in early morning) over frequent light watering, which encourages shallow rooting and disease development. Established turf that survives July heat intact has better winter hardiness and disease resistance entering dormancy in November.

Properties in new your lawn subdivisions offer unique challenges. During site development, heavy equipment compacts native soil, destroying soil structure and eliminating air-filled pores necessary for root respiration and microbial activity. When landscape contractors then apply 2–4 inches of imported topsoil over that compacted base, the root zone becomes a two-layer sandwich: loose topsoil over impermeable clay. Roots penetrate the topsoil quickly, hit the compaction barrier, and stop; water pooling at 4–6 inches below the surface. Plant stress follows: grass thins, fungal diseases establish, grubs proliferate in the cool, wet compaction zone. Core aeration breaks that compaction barrier, but only aggressive aeration (pulling 200+ cores per 1,000 sq ft) provides meaningful relief. We assess compaction severity with soil cores and recommend aeration strategy tailored to each property's building history.

Homes built in the 1980s and 1990s throughout the area now have 30+ years of grass growth. Accumulated dead shoots and rhizomes create a dense thatch layer 1–2 inches thick in many properties. That thatch layer insulates the soil surface, reducing water infiltration and nutrient availability to grass roots. It also becomes ideal habitat for grubs, chinch bugs, and fungal disease spores. Unlike fresh construction sites where compaction is the primary issue, established neighborhoods need thatch removal followed by core aeration. We use vertical mowing (dethatching) in late spring or fall to mechanically remove accumulated organic matter down to soil level, then follow with aeration and overseeding. This two-step process restores soil contact for grass roots and eliminates pest habitat layers.

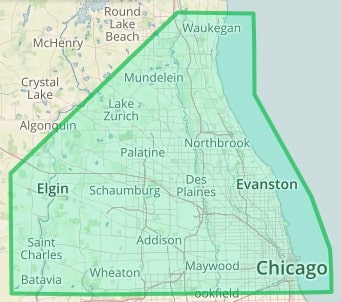

We also treat properties in these surrounding towns: