Shade Turf Management & Tree Care in Buffalo Grove

The grass really is Greener the way we treat it.

The grass really is Greener the way we treat it.

Buffalo Grove's mature residential neighborhoods are defined by dense tree canopy — 60+ year-old oaks, maples, and pines tower over homes spanning 60089. That shade, combined with acidic Cook County soils (pH 5.8–6.5), creates an environment where standard Kentucky bluegrass simply fails. Bluegrass requires 3–4 hours of direct sunlight daily; local properties receive 2 hours or less beneath dense canopy. Add acidic chemistry that locks available phosphorus and potassium, and bluegrass yellows, thins, and succumbs to shade-loving broadleaf weeds like Creeping Charlie.

Our program centers on hard fescue (Festuca trachyphylla), a cool-season species evolved for European shade forests. Hard fescue tolerates 30–40% shade, roots to 24–30 inches (reaching moisture in deeper acidic clay), and performs robustly across the pH 5.8–6.5 range that dominates local soils. We blend it with chewing fescue for additional shade tolerance and acidic-adapted bluegrass cultivars, creating a turf stand that fills bare patches over time while maintaining fine texture and density. Every property assessment includes a canopy density evaluation — if shade exceeds 50%, we recommend selective pruning to open the tree crown and improve light penetration for the new seed.

Acidic soils require different nutrient management than neutral or alkaline conditions. Phosphorus availability peaks in spring (March–April) when soil temperatures are still cool; applications after May are largely unavailable to plants. Soluble-sulfur fertilizers help maintain the 6.0–6.5 pH that favors fine fescue. We also apply chelated iron in April and again July to prevent the interveinal chlorosis that acidic soils often trigger in stressed turf.

Creeping Charlie (ground ivy, Glechoma hederacea) is Buffalo Grove's most persistent broadleaf challenge. This aggressive ground-hugging weed thrives in dense shade, acidic soils, and moist conditions — the exact environment beneath old-growth oak and maple canopies. Its shallow fibrous root system and prostrate growth allow rapid recovery from single herbicide applications. Standard spring broadleaf sprays kill shoots but leave roots intact for rapid resprouting.

We use a three-component strategy. Spring herbicide (May–June) targets young foliage and reduces seed head production, but doesn't kill the plant. Summer canopy pruning on overhanging oak/maple branches increases light penetration, promoting fine fescue vigor and competitive exclusion of Charlie. Fall herbicide (September–October), applied when Creeping Charlie moves carbohydrates to roots for overwinter hardening, achieves far superior root-tissue kill. The cool root-zone temperature extends herbicide residue life and biological activity. Immediate overseeding with shade-tolerant fine fescue then fills bare patches, and fine fescue's allelopathic compounds inhibit Charlie regrowth. Three-year programs produce near-complete Charlie elimination in most local properties.

"Our entire yard is under old maple trees and it was just dead zones and Creeping Charlie. After the first year with Greener Living's shade program, we had actual green grass. By year three, the Charlie is almost gone. The fine fescue they overseeded with is thriving where bluegrass never could."

— E. & M. Rodriguez, 60089

"Every spring our front yard would stay soggy for weeks. My previous lawn guy had no answer. Greener Living did fall aeration and explained it was clay compaction plus water table issues. One fall of aggressive aeration completely changed the drainage. No more May puddles."

— D. Chang, 60089

"Our 60-year-old oaks looked pale and stressed. They explained that acidic soil was locking up nutrients and the trees couldn't absorb iron despite it being in the soil. The deep-root feeding and dormant oil made a huge difference. New leaves came in dark green and the crown looks fuller again."

— C. & P. O'Brien, 60089

local properties combine mature-tree challenges with acidic-soil chemistry. We offer integrated programs:

Tell us about your mature trees, shade patterns, waterlogging history, and weed challenges. We'll recommend a site-specific plan.

Caymen personally evaluates local properties with significant shade and discusses long-term canopy management strategy.

pH-adjusted programs, chelated iron application, and phosphorus-timing strategies based on acidic-soil chemistry.

Creeping Charlie eradication, shade-turf establishment, and waterlogging relief take time. We commit to the full program with you.

Month-to-month service, no contracts. Pause or cancel without penalties if circumstances change.

Chicagoland's mix of old-growth canopy and acidic soils demands specialists who understand shade physiology and soil chemistry. We are locally-owned and transparent — when we recommend canopy pruning or three-year herbicide strategies, we explain the horticultural reasoning. You speak directly with the owner, not a regional call center with preset packages.

Buffalo Grove's acidic Cook County soils (pH 5.8–6.5) create fundamentally different turf management requirements than neutral or alkaline soils. In acidic conditions, phosphorus — the nutrient controlling root initiation and cold hardiness — becomes chemically unavailable despite being physically present in the soil. Clay particles bind phosphate ions at pH below 6.0, rendering them inaccessible to plant roots. This locking occurs faster as soil temperature rises; March–April phosphate applications penetrate quickly while May and later applications arrive too late. Potassium availability also declines in acidic soils, reducing cell-wall strength and winter hardiness. Iron, typically abundant in acidic soils, sometimes becomes overly available, triggering toxic accumulation; other times it binds to organic acids and becomes unavailable, creating the yellow interveinal chlorosis local residents observe in stressed trees. Kentucky bluegrass, shallow-rooted and adapted to neutral pH conditions, fails predictably in this acidic, shaded environment. Hard fescue and fine-leaf fescue, evolved for cool-forest soils across northern Europe, thrive at pH 5.8–6.5 with sufficient moisture access through deeper root systems.

Glechoma hederacea (Creeping Charlie, ground ivy) is endemic to Buffalo Grove's acidic, shade-dominated landscape. This biennial broadleaf weed persists through two complementary survival pathways: each season, Charlie produces seed that overwinters in soil, and simultaneously, existing plants overwinter as root crowns and rhizome fragments capable of regenerating an entire plant from 2-inch sections. Single herbicide applications kill shoots but never eliminate root reserves. Spring herbicide applications (May–June) target tender new foliage and reduce seed head production but do not cause meaningful root death. Summer canopy pruning — thinning overhanging oak and maple branches — increases light penetration and shifts competitive advantage to fine fescue, which releases allelopathic compounds that inhibit Charlie germination and growth. Fall herbicide (September–October), applied when Charlie has completed most root growth and begun carbohydrate storage for overwinter hardening, achieves superior root-tissue translocation and kill. The cool soil temperature and reduced microbial activity extending herbicide biological window into late fall means herbicide residue persists longer and penetrates deeper. Three-year programs combining all three tactics — spring spray, summer canopy work, fall spray — eliminate Charlie from most local properties by year three.

The area lies on glacial clay deposits left by Wisconsin-stage glaciation, predominantly illite and montmorillonite clay minerals with extremely low permeability. This clay layer, 20–40 feet thick in places, sits atop limestone bedrock. During spring thaw (March–May), snowmelt and heavy rains deliver 2–3 inches of water in weeks. That water cannot infiltrate into the clay; it pools on the surface or moves laterally into the groundwater system. The water table rises into the root zone — often 3–6 inches below the surface in low-lying local properties. Grass roots in saturated soil experience hypoxia (oxygen deprivation). Soil microbes switch to anaerobic respiration, producing toxic compounds (hydrogen sulfide, methane) that kill fine roots and promote pathogenic fungi. Ring-shaped dead patches appear where waterlogging concentrates. Core aeration addresses root-zone compaction that exacerbates the problem. By pulling soil cores at 2–3 inch spacing to 3-inch depth, we mechanically disrupt the compacted layer that prevents vertical water movement. Water then drains laterally into aerated zones instead of pooling on surface. Fall aeration (September–early October) is ideal: soil moisture from summer rains and early fall precipitation supports rapid healing of aeration wounds, and by mid-November, root systems have established around core holes to survive winter and manage spring inflow more effectively.

Your property's oldest neighborhoods (1950s–1970s) feature planted shade trees — oaks, maples, ash — that have grown 60+ feet tall and now cast near-total shade across many properties. At 20–30% full sunlight (typical of mature tree canopy at midday), even shade-tolerant turf grasses cannot photosynthesize at full capacity. Fine fescues decline at less than 20% light; hard fescue pushes tolerance to 30–40% but cannot survive 10% shade indefinitely. Assessment of canopy light load is critical before recommending tall fescue blends: if shade exceeds 50% (full sunlight only 2 hours at solar noon), selective canopy pruning becomes essential. Removing lower branches, thinning crowns by 10–15% (removing inner dead wood and crossing branches), and crown raising (removing lower lateral branches) can increase understory light to 25–35%, placing properties back in hard fescue's viable range. This work is done by certified arborists during late fall–early spring dormancy. Once canopy is opened, hard fescue overseeding establishes dense turf that excludes Creeping Charlie and other shade-loving broadleaves.

Phosphorus is the bottleneck nutrient in Buffalo Grove's acidic soils. This non-mobile nutrient controls root initiation, root elongation, and the energy metabolism of root cells. Deficient phosphorus produces shallow, poorly-developed root systems even in well-watered soils. In acidic clay, phosphate-fixation occurs when phosphate ions contact clay surfaces; the ions form insoluble compounds the soil cannot exchange or mobilize. This fixation accelerates with increasing soil temperature. March–April soil temperatures (40–50 degrees F) allow phosphate to diffuse into soil solution before clay fixation occurs. May–June temperatures (55–70 degrees F) dramatically accelerate fixation; by June, most applied phosphate is fixed within 2–4 weeks of application. By July (soil temps >75 degrees), virtually all phosphate applied is fixed within 1–2 weeks. Therefore, spring phosphorus application in late March or early April — immediately after soil thaw, before fixation accelerates — delivers maximum bioavailability. We time all Local phosphate applications to this narrow window. Nitrogen can be applied throughout the growing season without fixation concerns, so we separate our spring phosphate-rich fertilizer (March–April application) from our summer and fall nitrogen-focused applications.

Acidic soils contain abundant iron, yet mature trees in the area frequently display interveinal chlorosis (yellow leaves with green veins) typical of iron deficiency. The paradox occurs when root-zone soil pH and soil chemistry prevent iron from being in a form the tree can absorb. Additionally, compacted soil around mature tree bases (from foot traffic, construction, root space limitation) restricts the roots' access to what iron does become available. Shallow-rooted trees cannot reach deeper, less-compacted soil where microbes produce small amounts of available iron. Deep-root feeding — injection of chelated iron directly into the vascular tissue below the compaction layer — bypasses soil chemistry entirely. Results appear within 3–4 weeks as new leaf emergence shows normal green coloration instead of yellow interveinal pattern. Combined with dormant oil applications in March (suppressing scale insects, aphids, spider mites, and mites that exploit weakened trees), a three-year deep-root feeding program restores vigor to 60+ year-old oaks and maples, with visible crown fullness and color recovery by year two.

Get Your Custom Buffalo Grove Assessment → or call 224-415-3698

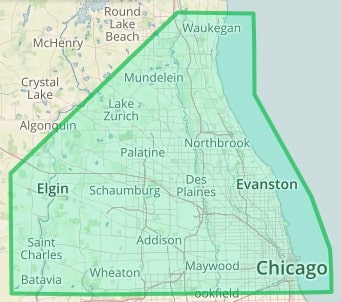

We also treat properties in these surrounding towns: