Salt-Tolerant Turf & North Shore Lawn Care

Lake Michigan salt spray + winter de-icing = specialized North Shore expertise.

Lake Michigan salt spray + winter de-icing = specialized North Shore expertise.

Deerfield's North Shore location brings competing challenges. Sandy loam soils provide excellent drainage and aeration — ideal for deep-rooting perennial ryegrass that grows thick, attractive turf. But Lake Michigan proximity creates salt-laden spray, winter desiccation from wind and low humidity, and intense de-icing salt applications on driveways and streets. Perennial ryegrass is moderately salt-tolerant but begins showing damage when soil salinity exceeds 1,000 ppm sodium. Winter salt spray burns foliage and accumulates in soil, making water unavailable even when moisture appears adequate. Late-winter and early-spring turf browning in the area is typically salt damage, not cold damage.

Our program prioritizes salt-tolerant ryegrass cultivars — varieties bred in coastal regions that genetically tolerate higher sodium concentrations without root toxicity. We supplement with soil salt remediation: spring cores to measure accumulated salinity, then deep irrigation in April–May to leach salts below the root zone before peak growth in June. Additionally, we reduce potassium fertilizer rates (high potassium can interfere with salt tolerance physiologically) and recommend calcium chloride or magnesium chloride alternatives to rock salt (sodium chloride) for driveway de-icing. Late-fall dormancy promotion (reducing nitrogen post-August) combined with anti-desiccant spray (waxy coatings that reduce transpiration) minimizes winter browning from desiccation and salt damage.

Sandy loam naturally encourages deep rooting; perennial ryegrass develops roots to 36+ inches if managed correctly. We encourage this depth through infrequent deep watering (1–1.5 inches per week applied once, not daily light applications) rather than frequent light irrigation that promotes shallow rooting. Deep-rooted turf tolerates summer drought far better than shallow-rooted turf, giving local properties resilience through dry July–August periods that sometimes plague the North Shore.

Winter road salt accumulates in soil at an average rate of 500–1,500 ppm sodium by late March (depending on application rate and rainfall). Once soil salinity exceeds 1,000 ppm in the root zone, grass begins showing damage: marginal burn, reduced growth, yellowing. We measure soil salinity using cores collected in April and recommend spring leaching strategy accordingly. For properties with salinity above 1,500 ppm, we recommend deep irrigation (1–1.5 inches applied once in a 4-hour window in April or early May) to push accumulated salt below the 6-inch root zone into groundwater. This one application can reduce root-zone salinity by 50–70%, preparing turf for healthy May–June growth. Call 224-415-3698 for a spring salt assessment.

"Our north-facing lawn was always brown from salt and wind. Greener Living explained spring leaching and switched us to a salt-tolerant ryegrass blend. First year after treatment, we had green turf in early April instead of the usual brown straw. Game changer for the North Shore."

— D. & K. Nielsen, 60015

"Near the lake, everything dried out. Caymen explained that deep irrigation (not daily light watering) builds deep roots. Our turf now survives the dry July spells that used to kill it. Deep watering really works."

— J. Hendrickson, 60015

"They took soil samples before and after spring treatment and showed us the salinity dropped from 1,400 ppm to 600 ppm. Concrete evidence that remediation works. Best explanation I've ever gotten from a lawn service."

— S. Braverman, 60015

local properties need integrated approaches combining salt tolerance, drought management, and lake-effect resilience:

Tell us about salt damage, winter browning, drought stress, and proximity to Lake Michigan — we'll recommend salt remediation and turf strategy.

We measure spring salinity and recommend leaching strategy with concrete data from soil cores.

Ryegrass cultivars selected for coastal salt tolerance & genetic resilience.

Deep-root development & irrigation timing for July–August dry spells.

Anti-desiccant coatings & dormancy management for winter stress & wind.

Local is not suburban turf — it's North Shore resilience. Salt, wind, drought, and winter desiccation compound in ways that standard programs cannot address. We specialize in the specific challenges: measuring and remediating soil salinity, selecting cultivars that thrive in salt-stressed conditions, and optimizing irrigation for deep rooting that survives Lake Michigan extremes. Our program is built on understanding North Shore hydrology and plant physiology under stress.

Deerfield's soils are post-glacial sandy loams deposited by melting ice-age glaciers and modified by Lake Michigan wind and water action over millennia. Sandy loams contain 50–60% sand, 20–30% silt, and 15–25% clay by particle-size distribution. This composition gives local soils high permeability (water and air move easily through pores) and freedom from waterlogging issues that plague clay-heavy soils. However, sandy loams also have low water-holding capacity — capillary water moves slowly upward to replenish plant-available moisture in the rooting zone, leaving turf vulnerable to drought stress in dry seasons. Winter road salt accumulation is the defining challenge: sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions deposited from de-icing applications move downward through sandy loam very efficiently, concentrating in the root zone by late winter. Spring soil cores in the area typically show 800–1,500 ppm sodium — well above the 500 ppm toxicity threshold for sensitive species and approach the 1,000 ppm damage threshold for moderately salt-tolerant grasses like perennial ryegrass.

The North Shore of Chicago was directly impacted by glaciation 12,000–15,000 years ago. Retreating glaciers left behind outwash plains (sandy, well-drained glacial melt deposits) and terminal moraines (ridge lines of accumulated glacial debris). Deerfield sits on outwash plains, resulting in the sandy loam soils that characterize the area. Lake Michigan formed in the glacial basin, and its shore has been retreating westward for 8,000 years due to isostatic rebound (the land is slowly rising after the disappearance of glacial weight). This geological history creates Deerfield's unique horticultural profile: excellent drainage and aeration (ideal for deep rooting) but high salt vulnerability due to sandy loam's rapid permeability that doesn't buffer salt ions. Understanding this glacial history explains why Deerfield turf management is fundamentally different from inland Chicago or western DuPage suburbs with clay-based soils.

Perennial ryegrass has a salinity tolerance threshold around 800–1,000 ppm sodium. Above that, root cells experience osmotic stress — the soil solution becomes hypertonic relative to root cells, drawing water out of the plant and toward the soil. Additionally, Na+ and Cl− ions that accumulate in leaf tissue interfere with photosynthesis at the enzyme level, reducing carbon fixation efficiency. Grass shows marginal burn (leaf edges brown and die while green tissue remains in the center), reduced growth, and eventual thinning if salinity persists. Salt-tolerant ryegrass cultivars (such as those bred at coastal universities in Oregon, California, and Scandinavia) have enhanced vacuolar compartmentalization — the ability to store sodium and chloride in vacuoles (cell storage compartments) rather than in cytoplasm, preventing enzyme damage. Selection of these coastal-adapted cultivars is essential for the area. Additionally, reduced potassium fertilizer during spring (competitive inhibition: potassium and sodium compete for root uptake sites) optimizes salt tolerance physiology.

Deerfield's lake-proximate location creates winter extremes. Lake Michigan moderates air temperature but creates persistent wind and low humidity. At temperatures below 0°C, grass shoots are frozen; water cannot move from roots upward. Simultaneously, frozen grass blades lose water through transpiration — stomates remain partially open despite freezing, and water vapor escapes. Exposed grass blades on windward slopes show rapid desiccation: tissue dehydrates, becomes brown and brittle (straw appearance), and cannot recover until spring thaw allows root water uptake. Properties within 0.5 miles of the lake experience 40–60% worse desiccation than inland local properties. We mitigate by: (1) late-fall nitrogen reduction (low nitrogen promotes dormancy and reduced transpiration rates), (2) anti-desiccant spray in late November (waxy coatings that reduce water vapor escape), (3) shelter plantings (windbreaks that reduce wind speed at the turf surface). These combined approaches reduce desiccation damage by 50–70%.

By late March, accumulated winter salt typically reaches 1,000–1,500 ppm sodium in the top 6 inches of local soil — well into the damage threshold for all but the most salt-tolerant species. Deep spring irrigation (1–1.5 inches applied in a concentrated 4-hour window in April or early May) creates a wetting front that pushes salt ions downward through the soil profile, moving them below the active rooting zone (top 6 inches) into deeper layers and eventually into groundwater through leaching. This one application can reduce surface salinity by 50–70%, from 1,400 ppm to 600 ppm, removing the osmotic stress that inhibits spring growth. Timing is critical: leaching must occur before major root growth in May–June (the critical spring growth window). We measure baseline salinity with soil cores in March, recommend leaching strategy, then verify effectiveness with post-leaching cores. This data-driven approach shows homeowners concrete evidence of remediation effectiveness.

Perennial ryegrass is a true deep-rooting species, capable of developing roots to 36–48 inches in uncompacted sandy soils if irrigation management encourages depth. However, frequent light watering (daily or every-other-day applications) promotes shallow rooting — roots stay in the upper 2–4 inches where moisture is regularly replenished. Your property's dry summers (often <0.5 inches rainfall in July–August) expose shallow-rooted turf to severe drought stress. Instead, infrequent deep watering (1–1.5 inches per week applied once in a 4-hour window) forces roots to develop deeper to access moisture stored at depth. By mid-summer, deep-rooted turf survives 2–3 week drought periods; shallow-rooted turf wilts within days. We coach Deerfield customers on irrigation timing (early morning watering to minimize evaporation) and recommend smart irrigation controllers that reduce frequency during rainy periods and increase depth during dry spells. Deep-rooted turf tolerates the "green and gold" nature of North Shore precipitation patterns.

local soils have pH 7.0–7.5, slightly alkaline, due to glacial-deposit limestone content. At pH above 7.0, iron precipitates into ferric oxide forms (Fe2O3) that plant roots cannot absorb. Perennial ryegrass is moderately susceptible to iron chlorosis under high-pH conditions — new leaf tissue emerges yellow, with green venation remaining. Additionally, excess potassium (often accumulated from de-icing salt runoff) can interfere with iron uptake by competing for root absorption sites. We address this through chelated iron applications (ferrous sulfate, citrated iron) applied in spring and early summer when chlorosis symptoms first appear. Soil cores measuring pH and extractable iron concentration help diagnose severity. Reducing potassium fertilizer during spring (March–April) optimizes the potassium:iron uptake ratio, reducing chlorosis risk. Most local properties benefit from chelated iron applications every 1–2 years.

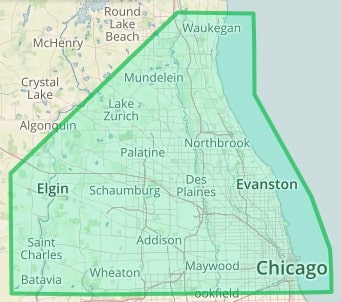

We also serve properties in these surrounding North Shore towns: